If you speak with Florence Welch on any normal day, it is fair to assume she feels a touch of anxiety. “Anxiety is the constant hum of my life,” she admits. “Then I step out onstage, and it goes away.”

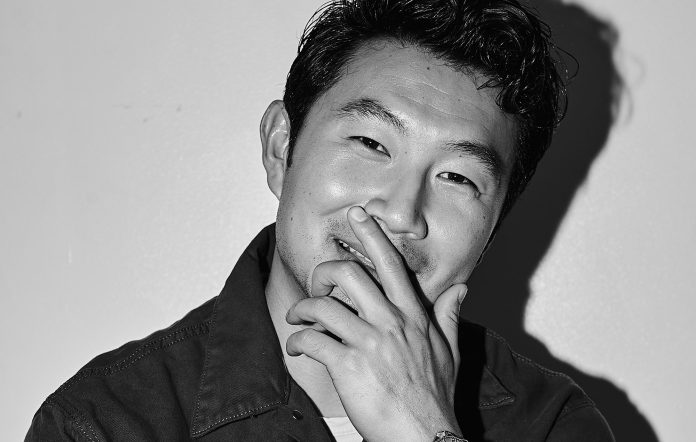

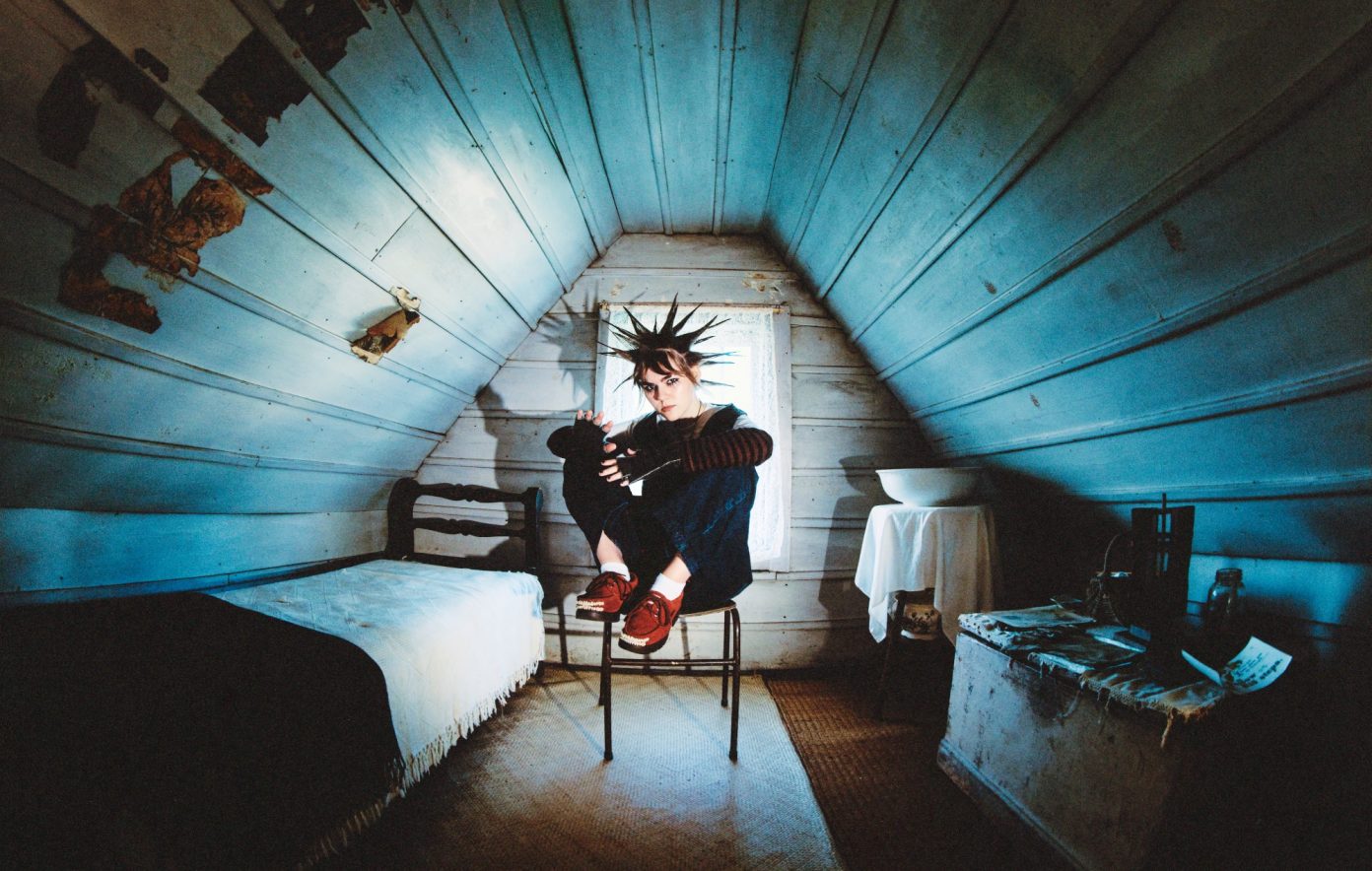

At this moment, that is exactly where she is. Draped in a long white gown, she sits comfortably before a 150-person crowd at New York’s Cherry Lane Theatre, a historic downtown space known as the birthplace of off-Broadway theater. It is one week before the release of Everybody Scream, the compelling sixth album she recorded with her band Florence + the Machine. Welch is here for the debut live edition of The Rolling Stone Interview, the magazine’s long-running in-depth conversation series. (This event also marks the first video podcast version of the franchise, available on Rolling Stone’s YouTube channel and all major podcast platforms.)

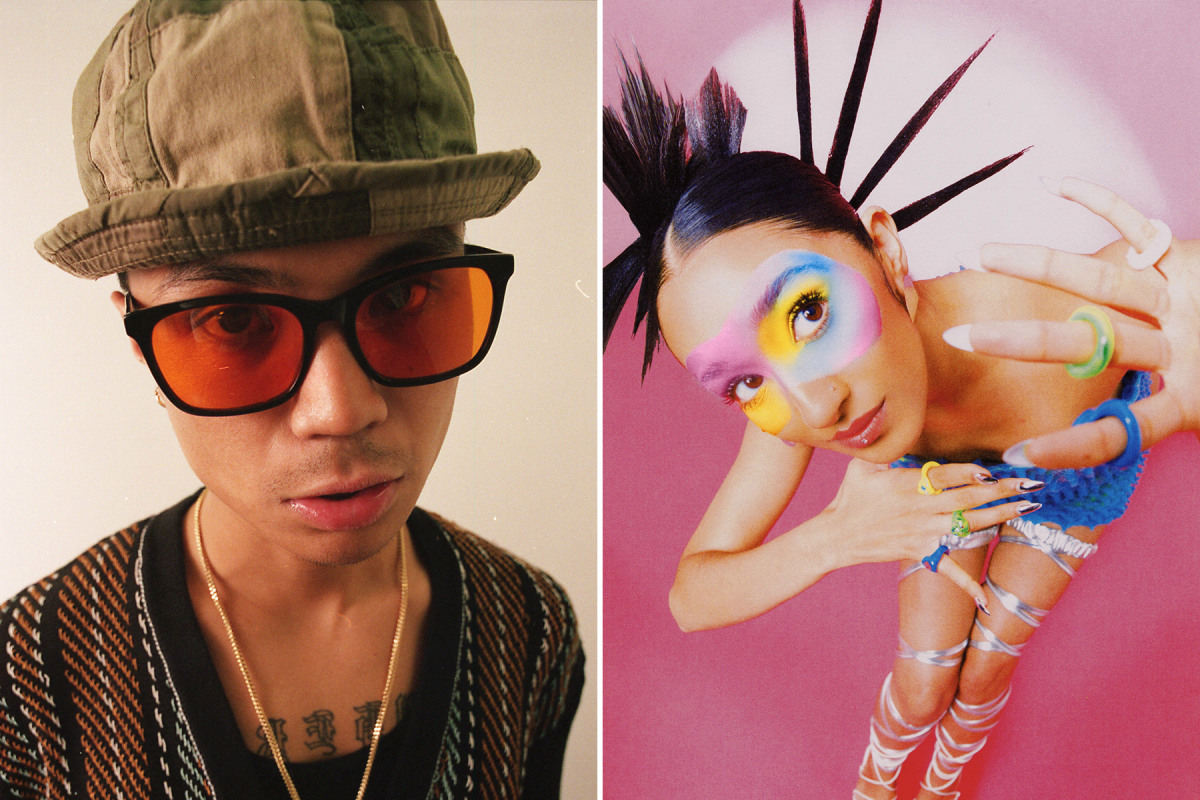

During both the interview and an intimate acoustic performance, the energy in the room mirrors the intensity of her new record, even when the discussion turns to darker themes. Created alongside collaborators such as Aaron Dessner of the National, Mark Bowen of Idles, Mitski, and James Ford, Everybody Scream is both visceral and spiritual, capturing Welch’s reflections on life, grief, and renewal. It also highlights her extraordinary voice, which has remained one of the defining instruments in popular music since her band’s 2009 debut. The songs were inspired by experiences on her 2022 Dance Fever tour, where she endured an ectopic pregnancy and a ruptured fallopian tube that required emergency surgery to save her life.

Throughout the conversation, Welch balances honesty with quiet humor as she reflects on her creative growth and how her music has evolved. “The calmer my life got, the wilder I could be in my performance styles and in my videos and in my artwork,” she reflects midway through the talk. “I found that freedom from shame means that you can explore so many more different things in your work, and I really found that to be amazing.”

The story of this album starts with your last tour, for 2022’s Dance Fever. Can you tell me about going into that tour and how you left as a different person after it?

I think Dance Fever was a record of prophecy, and this one became a record of catastrophe. That album dealt with performance and the experience of losing it entirely. There was a period when no one knew if live music would ever return, and it made me question whether I wanted to keep doing this or start a family instead. Then, on that tour, I had a life-changing experience that led directly to making this record.

Everybody Scream grew out of a desire to explore magic and mysticism more deeply. It felt as though things I had imagined were coming true, and I needed to understand what was happening. It opened a space for me to examine different sides of myself while I was going through something so profound.

Have you ever had an album or song prophesize what came after?

Never this literally. I wrote a song for Dance Fever called “King,” where I wrestled with whether I wanted to be a mother. There is a line in it that goes, “I never knew my killer would be coming from within.” What almost took my life was a complication from a pregnancy loss onstage. I never expected it to be that literal.

What brought you to study more magic and mysticism?

When something happens to your body like that, you feel powerless. I started searching for some form of strength and felt drawn to something primal. It happened so suddenly and violently, but it saved my life. When you are rushed into emergency surgery, the lights are blinding and everything feels sterile and detached. Afterwards, I felt an overwhelming need to reconnect with the earth and with nature.

Wherever I looked—stories of birth, life, and death—I found recurring threads of witchcraft and folklore. You cannot explore those subjects without encountering tales of witches or magic, because they represent the mysteries we still cannot explain. No one could tell me why what happened to me occurred. They only said it was “bad luck.” When no one has an answer, you begin to search for meaning, for understanding, and for some sense of control.

You experienced pregnancy loss onstage, while performing in front of thousands of people. How did you navigate that as a performer?

I was in pain. And what do you do as a woman? You take some ibuprofen and keep working. I was in a space I understood, where my body usually felt strong and capable, yet I was going through something devastating. I didn’t realize it was dangerous at the time. I just thought, “If I can make it through this show, at least I won’t feel like I’ve lost everything.” When I walked onstage, the pain disappeared, and I felt completely free. It turned out to be an incredible show, even though I was unknowingly bleeding internally. I had no idea I was in real danger. Still, there was a familiar presence that I always feel when I perform, something that lifted me and carried me through. It felt almost like love. I was standing in the middle of chaos, yet there was beauty in it. It sounds strange to say, but it was powerful.

Did you start working on or writing the album shortly after, or did it take some time to process?

I had already begun making the album. The first person I worked with was Mark Bowen from Idles. When both of us had breaks between tours, we would meet to sketch out ideas. “One of the Greats” had started to take shape, and I believe “Everybody Scream” followed. I went straight from touring into the studio because I needed to process what had happened.

Afterwards, I began trauma therapy with a specialist who works with people who have been through similar experiences. She was wonderful. She told me that many people feel an urge to fix everything quickly, sometimes by trying to have another child right away. She said, “The only advice I can give you is to wait until you feel like yourself again.” For me, I only ever feel like myself when I am creating music, so that became my way of healing.

I barely remember the first six months of recording. Early songs like “Witch Dance” and “You Can Have It All” were written almost immediately after everything happened, and my memory of that time is blurred. What made that period special was working with Bowen, whose sound carries a raw, punk-like intensity. It was exactly what I needed. What happened to me was violent and dissonant, and the music reflected that. It felt right that we were already collaborating, because he was the perfect person to help me write through the chaos that followed.

Was it that same concert review or a different moment that spurred you to consider the limitations of how women are perceived in the industry?

You see it all the time in lists and rankings. There’s often a quota — a certain number of women they feel they can include before deciding they’ve filled that space.

To be honest, I never really felt connected to my gender in a strict sense, and even now I’m not sure what it truly means to be a woman. I don’t assign any particular qualities to it. Because of that, I never felt limited by it early on. It took getting older to realize that not everyone took me seriously when I was younger, and that much of it had to do with being a young woman. I used to think people dismissed me because I was simply annoying or too much. Only with time do you see the pattern repeating with other women and recognize, “Maybe that wasn’t just me.”

That understanding comes with experience, but it also brings anger. This album wrestles with what it costs to devote yourself entirely to this life and to the stage. I spoke with Mitski about that, and she said, “Yes, but the intimacy that kind of commitment gives you — the closeness to your art and your performance — is something extraordinary.” I feel that deeply as well.

And when you step outside of all the trappings of being a rock star onstage and putting out an album, what does your life look like?

It’s actually quite ordinary. That’s the balance I’ve learned to maintain — calm in my daily life so I can be wild in my creative one. That’s proven true for me. The quieter my life became, the more freedom I found to be expressive in my performances, my videos, and my art.

There was a time when I was struggling with shame, insecurity, and self-destructive habits. I drank and used substances to make sense of those feelings. Once I became sober and my life slowed down, I realized that being free from shame allowed me to explore more creatively than I ever had before. That discovery was transformative.

When I’m home, my days are slow — lots of pacing, reading, and watching television. Touring makes you long for rest, but the moment I’m back, I start to feel restless again. There’s a part of me that always wants to move, a creative energy that doesn’t sit still. I think, “I’m not meant for this calm domestic life. I feel too big for this space.” The fame-related parts of my job don’t hold much appeal. They mostly make me anxious.

Like what?

There’s a line in “Sympathy Magic” that mentions “the vague humiliations of fame.” That phrase sums it up well. Fame, for me, has often felt like a series of small embarrassments. The celebrity aspect has never really appealed to me.

Because I’m naturally shy and tend to feel anxious, I need plenty of time alone to think and to daydream. I need space away from the spotlight. I don’t actually enjoy being the center of attention. When the focus isn’t on my work, it makes me uncomfortable. I prefer to live quietly and privately when I’m not performing.

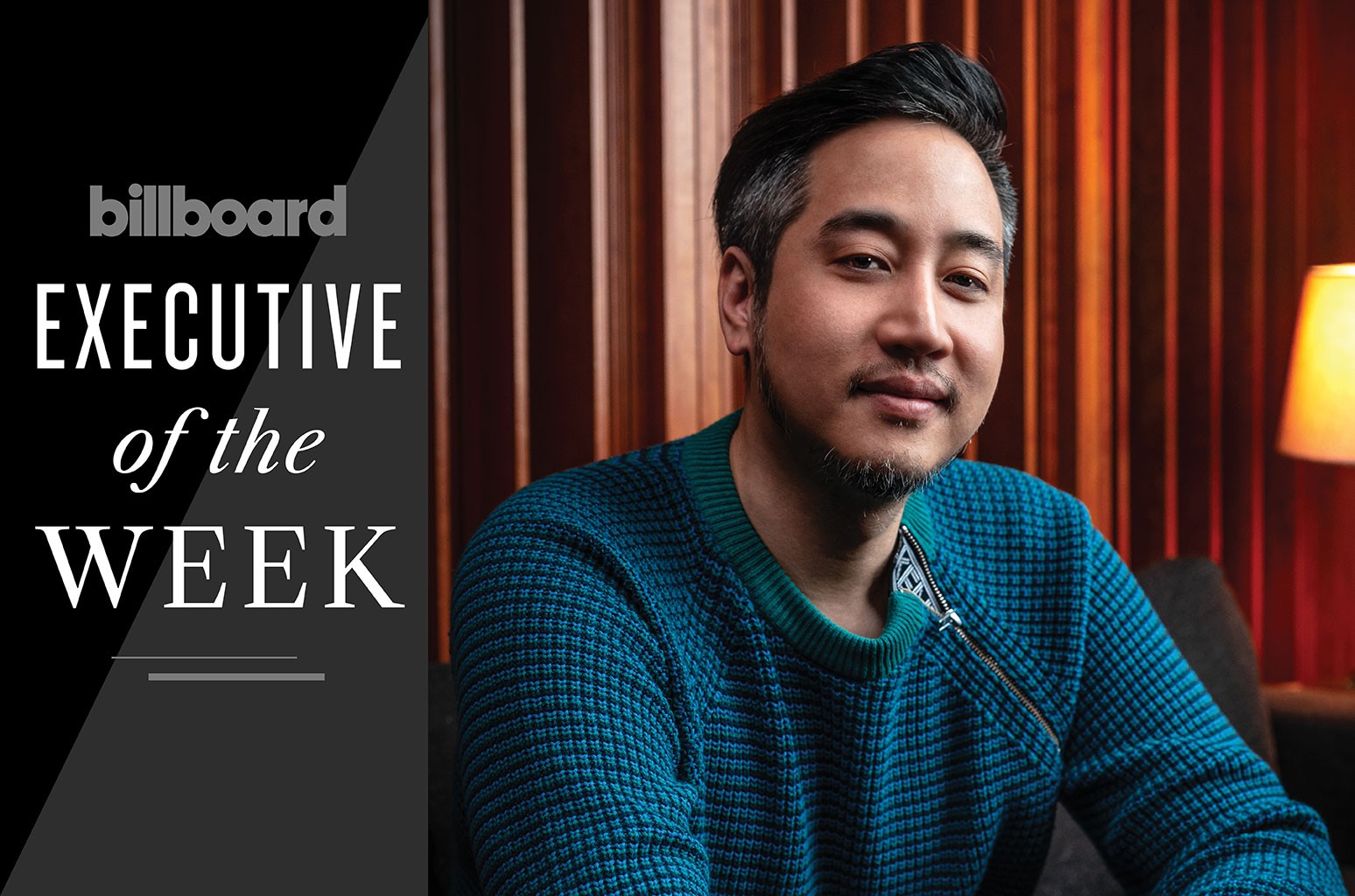

One of the first people that you called for this album was James Ford, who also worked on your breakthrough hit “Dog Days Are Over.” What do you recall of making a song that would end up changing your life?

I still have the CD with the original “Dog Days” demo on it. We were rehearsing at a place called Premises Rehearsal Studios in East London, which is still there. James had his studio upstairs, and I went and knocked on his door. He says I came in, started banging on the table, and sang it to him. The label I was working with at the time didn’t understand the demo at all. They said, “No, we need another ‘Kiss With a Fist’—something catchy and guitar-driven.” But James got it immediately.

The first thing he did was speed the song up a few beats per minute. It completely changed the feel. Years later, when I needed a lead single for this album, the demo for “Everybody Scream” was wild and a bit chaotic, and once again, James understood it right away. The first thing he did was speed it up. I thought, “All right, I trust you. That worked perfectly the last time.”

Have you had any mentors throughout your career?

Nick Cave has been incredibly kind to me. Nick and Susie Cave have both been such generous and supportive friends. I once sent Nick some of my poetry, and he helped me edit it. During tours, I would write him anxious emails, and he always responded with kindness and understanding. As someone who performs with such physical intensity himself, he understood what I was putting my body and mind through. He truly is one of the most compassionate people I’ve ever known.

On “One of the Greats,” you sing that you felt that you were “burned down at 36.” Do you still feel that way?

I actually think that when I turn 40, I’m going to feel amazing. I really do. It’s strange how, as you approach a new decade, everything starts to feel heavier. But I believe that once I reach 40, I’ll feel youthful again. There was a sense of urgency surrounding this record — I needed to release it now. If I hadn’t, I’m not sure I ever would have. This album is tied closely to where I am in life and what I’ve been through.

If I had waited longer, my perspective might have changed, and the emotions behind it could have softened. I’m grateful I was able to finish it, because what it speaks to is something so quiet and unspoken that many people endure. The idea of this album not being completed made me deeply sad. I’m thankful we managed to bring it to life and release it into the world.

.png)

.png)

.png)